Not everyone's a Taylor Swift fan, and that's fine. But as the first artist ever to raise a billion purely on music sales alone, you have to admit she's doing something right. So whatever kind of creative you are, there's a lot you can learn from her. And that's especially true of her latest big news.

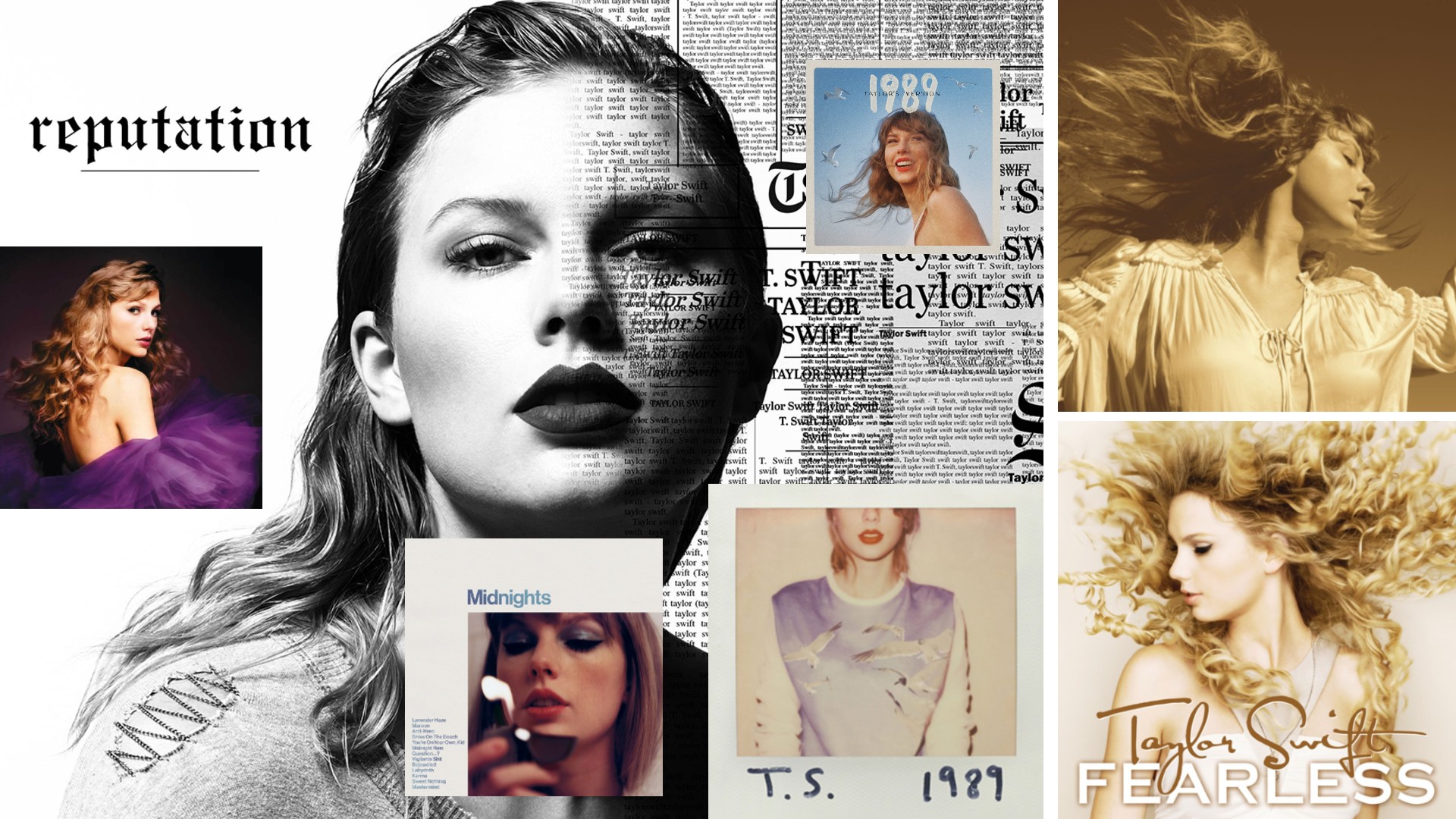

"All of the music I've ever made now belongs to me," Taylor Swift announced last Friday in a letter, finally ending a six-year saga that's generated more headlines than some actual wars. She lost the rights to her back catalogue in 2019, when her music manager Scooter Braun and his media holding company, Ithaca Holdings LLC, acquired her old label, Big Machine Label Group. And ever since then she's pursued a twin strategy: fighting to buy her music back, and systematically re-recording fresh versions of her past albums, dubbing each "Taylor's version".

Now Taylor has finally succeeded in buying back the originals from Shamrock Capital (which means we might not get Reputation Taylor's Version after all). It's the creative equivalent of your ex stealing your diary, so you rewrite it from memory with better jokes and nicer doodles, then buy back the original just to rub their face in it.

But what does this mean for creatives in general? Is this a path we should all follow? Should we spend our careers vigorously striving for ownership of everything we make? Turns out that's quite a tricky question to answer (and not just because of the implications of AI on copyright)...

When ownership doesn't matter

I'll start by pointing out I don't own a single word I've ever written professionally. Not one article, one book, not even the deathless prose you're reading right now. My entire career's output belongs to various publishers, magazines and websites scattered across the media landscape like literary confetti. And you know what? I'm fine with that (just as I was fine when Meta stole my book for AI, but that's another story).

I've spent two decades happily trading my words for money, and it's worked out pretty well. The publications I write for handle the marketing, distribution, legal faff, and general business hassles that would send me into a spiral of administrative despair. At the same time books such as my latest release, The 50 Greatest Designers, have been translated into dozens of world languages; something I'm again very happy for others to handle.

People pay me, I write things, everyone's happy. It's like having a literary sugar daddy, but with fewer awkward dinner conversations. I know many writers, artists, illustrators, designers and developers who feel similarly. I'm sure you do too. Maybe you're one of them.

So I think it's fair to say not everyone needs to own their content. However, what's equally important is that everyone should understand what they're giving up when they don't. Forewarned is forearmed.

When ownership actually matters

Certainly, there are times when owning your content is important. You might be creating something with serious long-term commercial potential, which could become a licensing goldmine a decade from now. Alternatively, it might be something so personal, the thought of someone else profiting from it makes you want to punch a wall. Or a bit of both.

Musicians, on the whole, are a perfect example of this. Your song could be earning royalties for decades, getting licensed for films, games, even the best adverts or suddenly blowing up on TikTok and YouTube for no discernible reason.

If you're a photographer, too, your images might appreciate in value, or become culturally significant further down the line, for all sorts of reasons. Similarly fiction writers who create characters or worlds might be sitting on potential franchise treasure.

For some creative disciplines, that's less likely, but there's always a chance what you create could sustain you in later life. Even for me: it's not unknown for magazines articles and non-fiction books to get turned into movies or TV series (Men Who Stare At Goats and Netflix's Inventing Anna both spring to mind.)

The same principle holds for illustration, graphic design and other visual disciplines. For example, one of the best logos – Milton Glaser's 1977 I love NY Logo – was done for the city for free, but imagine the revenue he'd have got if he'd licensed it.

How to protect yourself

But here's where it gets interesting: even Taylor Swift didn't start out owning everything. She signed away her masters as a teenager because that's how the industry worked. The difference is that when she got powerful enough to demand better terms, she did.

Assuming we're not all going to make a billion, though, the rest of us need to be smarter from the beginning.

What does that mean? First, read everything. Yes, contracts are duller than a watching slow-drying paint dry in slow motion. But understanding what you're signing is crucial. If you're selling your work outright, at least know what you're getting paid for that privilege.

Consider hybrid models. Maybe you retain some rights whilst licensing others. Perhaps you keep the rights but give someone else exclusive use for a specific period. There's middle ground between total surrender and complete control.

Build reversion clauses into contracts where possible. If your work isn't being actively exploited after a certain period, the rights should come back to you. This is particularly important for writers and artists whose work might find new audiences years down the line.

Being realistic

That doesn't mean you can demand everything you want from the word go, though. Unfortunately, the world doesn't work like that.

A more realistic path for freelancers and creators just starting out is to focus on building your reputation first. Yes, ownership is lovely, but paying rent is lovelier. Take the work that's offered, learn the business, then gradually negotiate better terms as your value increases.

Most importantly, don't let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Taylor Swift's story is inspiring, but it's also the exception. She had the money, fame, and fanbase to (eventually) get everything she wanted. Most of us don't, though, and that's fine.

The real lesson from Swift's victory, then, isn't that everyone should own everything—it's that understanding your rights and the value of your work is essential. Whether you choose to sell it or not is about making a conscious decision based on your circumstances, not blind acceptance of industry norms.

And for me? I'll continue happily selling my words to whoever wants them, secure in the knowledge that I'm trading ownership for professional peace of mind. But I'll also keep one eye on the contracts and one hand on my rights, just in case I ever create something worth fighting for. After all, you never know when you might need to pull a Taylor.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Tom May is an award-winning journalist and author specialising in design, photography and technology. His latest book, The 50th Greatest Designers, was released in June 2025. He's also author of the Amazon #1 bestseller Great TED Talks: Creativity, published by Pavilion Books, Tom was previously editor of Professional Photography magazine, associate editor at Creative Bloq, and deputy editor at net magazine.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.